When you take a medication like warfarin, tacrolimus, or levothyroxine, a tiny change in your dose can mean the difference between healing and hospitalization. These aren’t just any drugs-they’re narrow therapeutic index drugs, or NTI drugs. And if you’re switching from a brand-name version to a generic, you need to know what that really means for your health.

What Makes a Drug a Narrow Therapeutic Index Drug?

NTI drugs have a razor-thin line between working and causing harm. The FDA defines them as medications where even small changes in blood concentration can lead to serious side effects, treatment failure, or death. Think of it like walking a tightrope: one misstep, and you’re in trouble.

These drugs don’t have a wide safety margin. For example, warfarin-a blood thinner-needs to keep your blood just thin enough to prevent clots but not so thin that you bleed internally. Too little, and you risk a stroke. Too much, and you could bleed out. That’s why doctors regularly check your INR levels when you’re on it.

Other common NTI drugs include:

- Immunosuppressants: tacrolimus, cyclosporine, sirolimus

- Anticonvulsants: phenytoin, carbamazepine

- Antiarrhythmics: digoxin, flecainide

- Thyroid hormone: levothyroxine

- Aminoglycoside antibiotics: gentamicin

- Targeted cancer drugs: axitinib, nilotinib

As of January 2024, the FDA officially recognizes 33 drug products across 14 active ingredients as NTI drugs. That number is growing-new cancer therapies and biologics are being added because their effects are so precise, even minor dosing errors can be dangerous.

Why Generic Substitution for NTI Drugs Is Risky

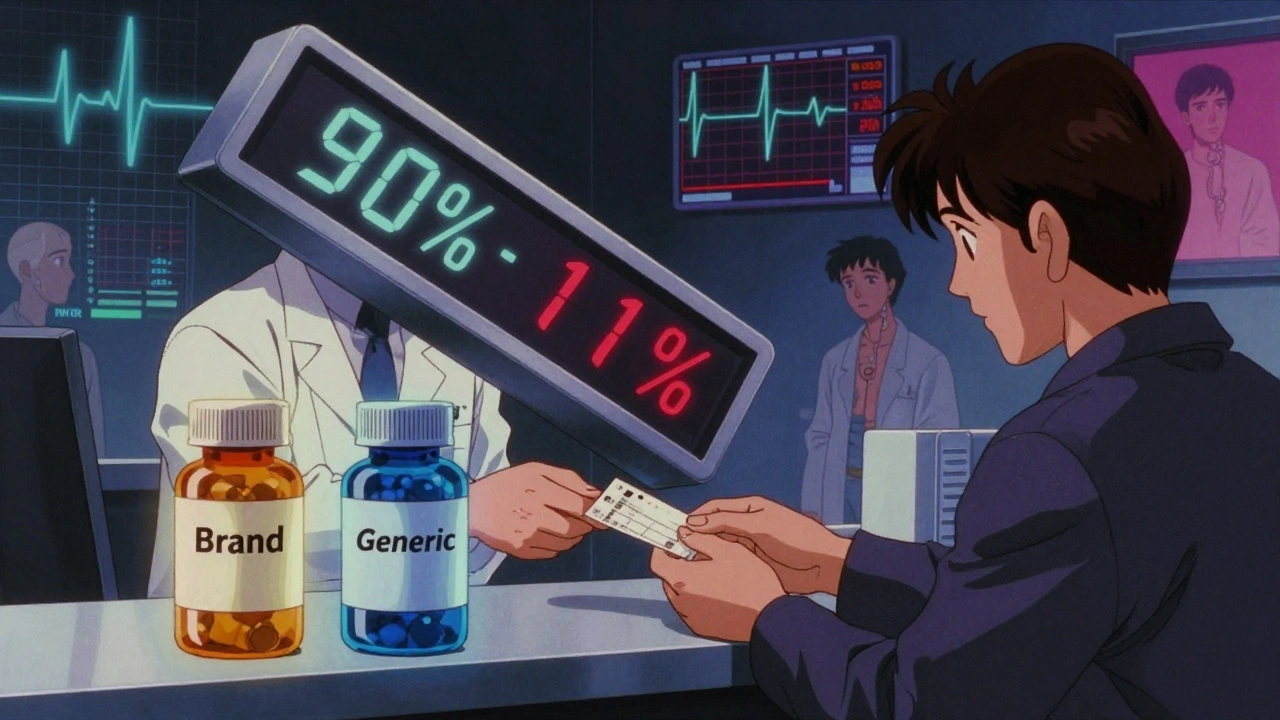

Most generic drugs are considered safe to swap with brand names because they meet the standard bioequivalence rule: their blood levels must be within 80% to 125% of the original drug. That’s a wide range. For most medications, it doesn’t matter if your blood level is 10% higher or lower.

But for NTI drugs, that 80-125% range is too loose. A 20% drop in blood concentration could mean your transplant is rejected. A 20% spike could mean organ toxicity.

That’s why the FDA created stricter rules for NTI generics. Instead of 80-125%, the acceptable range is often 90-111%. For some drugs with very low variability, like levothyroxine, it’s even tighter: 95-105%. This means manufacturers must prove their generic version behaves almost identically to the brand in your body.

Still, even with tighter standards, problems happen. A 2019 national survey found only 28% of pharmacists felt comfortable substituting generic NTI drugs for new prescriptions, compared to 78% for non-NTI drugs. Why? Because real-world data shows patients often have trouble maintaining stable levels after switching.

Real Stories: When Generic Swaps Go Wrong

Behind every statistic is a person. On patient forums, stories are common:

- A kidney transplant patient switched from brand Prograf to generic tacrolimus. Three weeks later, his creatinine levels doubled. He was hospitalized for acute kidney injury.

- A woman on levothyroxine for hypothyroidism had her insurance switch her to a different generic. Her TSH levels jumped from 3.2 to 12.8. She gained 15 pounds, felt exhausted, and couldn’t concentrate at work for months.

- A man with epilepsy had been seizure-free for five years on brand Dilantin. After switching to a generic phenytoin, he had two seizures within a week.

But not all stories are negative. Some patients report no issues. One epilepsy patient on PatientsLikeMe said he’s been on generic phenytoin for five years with perfect control and saves $300 a month. That’s the catch: some people do fine. Others don’t. And there’s no way to predict who falls where.

How the FDA and Pharmacists Handle NTI Drugs

The FDA doesn’t just set standards-they enforce them. For drugs like tacrolimus, phenytoin, levothyroxine, and carbamazepine, they require special replicate bioequivalence studies. These aren’t simple one-time tests. They involve multiple doses over several days to measure how the drug behaves in the same person repeatedly. This gives a clearer picture of consistency.

Pharmacists are trained to recognize NTI drugs. But here’s the problem: state laws vary. As of 2023, 42 states have laws restricting automatic substitution of NTI drugs. Some require the prescriber to write “dispense as written.” Others require patient consent. A few don’t have any rules at all.

That’s why many pharmacists will call your doctor before switching your NTI drug-even if the law allows it. They’re protecting you. And if you’re on one of these drugs, you should expect that call.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

If you’re prescribed an NTI drug, here’s what you need to do:

- Ask your doctor: Is this drug on the FDA’s NTI list? If so, ask them to write “dispense as written” on the prescription. This stops pharmacies from swapping it without permission.

- Know your brand: If you’re doing well on a specific brand or generic manufacturer, stick with it. Don’t let your pharmacy switch you to another version without telling you.

- Get regular blood tests: For drugs like warfarin, tacrolimus, or phenytoin, blood level monitoring isn’t optional-it’s essential. Make sure your labs are scheduled and results are reviewed by your provider.

- Track symptoms: If you feel different after a refill-more tired, dizzy, shaky, or having new side effects-contact your doctor. Don’t wait. It could be a change in the generic version.

- Ask your pharmacist: When you pick up your prescription, ask: “Is this the same manufacturer as last time?” If not, ask if it’s safe to switch.

Don’t assume all generics are the same. Even two different generics of the same drug can behave differently in your body. That’s why consistency matters more than cost.

The Cost vs. Safety Trade-Off

Generics save money. For many drugs, that’s a win. But for NTI drugs, the savings can come with hidden costs: extra doctor visits, emergency room trips, hospital stays, and lost work time.

One study found patients on NTI drugs with comorbidities like diabetes or heart failure had a 20-30% higher risk of drug-related problems after switching generics. That’s not a small risk. It’s a serious one.

Some insurance plans push for the cheapest generic-even for NTI drugs. If yours does, you may need to appeal. Your doctor can submit a letter of medical necessity. Many insurers will approve the brand if you can show that switching caused problems before.

What’s Changing in the Future

The field is evolving. The FDA plans to issue 12 new product-specific guidances by 2025, focusing on newer cancer drugs like neratinib and axitinib. These drugs are becoming more common, and their narrow therapeutic windows demand better control.

Pharmacogenomics is also entering the picture. By 2028, experts predict 40% of NTI drug prescriptions will include genetic testing to predict how you metabolize the drug. For example, some people are slow metabolizers of warfarin-they need much lower doses. Genetic tests can help personalize dosing from day one.

Internationally, harmonization is still a challenge. The FDA, EMA in Europe, and PMDA in Japan all have different ways of defining NTI drugs. That makes global drug development harder and creates confusion for travelers or patients using imported medications.

Bottom Line: Don’t Treat NTI Drugs Like Regular Medications

Narrow therapeutic index drugs are not like your daily ibuprofen or allergy pill. They demand precision. And while generic versions can be safe, they’re not interchangeable without careful oversight.

Your health isn’t a cost-saving experiment. If you’re on an NTI drug, treat it like a high-stakes medication-because it is. Stay informed. Ask questions. Demand consistency. And never assume that a generic is automatically safe to swap.

The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to empower you. You have the right to know what you’re taking-and to demand the right version for your body.

Are all generics unsafe for NTI drugs?

No, not all generics are unsafe. Many patients take generic NTI drugs without issues. But the risk of variation is higher than with regular drugs. That’s why consistency matters-staying on the same manufacturer’s version is often safer than switching between generics. Always monitor your response and report changes to your doctor.

Can I ask my doctor to prescribe only the brand-name version?

Yes. You can-and should-ask your doctor to write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on your prescription. This legally prevents the pharmacy from switching your medication without your doctor’s approval. Many insurers will still cover the brand if you provide documentation of prior problems with generics.

Why do some people do fine on generics while others don’t?

Everyone’s body absorbs and processes drugs differently. Factors like age, liver/kidney function, diet, other medications, and even gut bacteria affect how a drug behaves. For NTI drugs, even small differences in absorption can push levels into unsafe ranges. One person’s stable dose might be toxic for another.

How do I know if my drug is on the FDA’s NTI list?

Check the FDA’s website for their list of Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs, which is updated regularly. Your pharmacist can also tell you if your medication is classified as NTI. Common ones include warfarin, levothyroxine, tacrolimus, phenytoin, and digoxin. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor or pharmacist directly.

Should I avoid generics entirely if I’m on an NTI drug?

Not necessarily. Many people use generics safely. But you should avoid switching between different generic versions or from brand to generic unless your doctor approves it and monitors your levels closely. If you’re doing well on a brand, staying on it may be the safest choice. If you switch, be prepared for more frequent blood tests and close follow-up.

Next Steps: What to Do Today

- Review your current medications. Are any on the NTI list?

- Check your last prescription. Does it say “dispense as written”?

- Call your pharmacy. Ask what generic manufacturer you’re getting-and if it’s changed recently.

- Schedule your next blood test if you’re on warfarin, tacrolimus, phenytoin, or levothyroxine.

- Talk to your doctor about your concerns. You’re not overreacting-you’re being responsible.

Comments (8)

Linda Migdal December 1 2025

Let’s be real-this isn’t about generics. It’s about Big Pharma’s lobbying power. The FDA’s ‘tighter’ 90-111% range? A joke. They let companies game the bioequivalence studies with cherry-picked subjects. I’ve seen the data. One generic manufacturer used 12 healthy young males in a controlled lab. Real patients? Older, diabetic, on six other meds. They’re not testing the right people. And now we’re told to ‘trust the system’? No thanks.

ANN JACOBS December 3 2025

Thank you for this comprehensive and deeply necessary overview. As a clinical pharmacist with over twenty years of experience managing complex polypharmacy cases in elderly populations, I cannot emphasize enough the critical importance of medication consistency when dealing with narrow therapeutic index agents. The physiological variability among individuals-particularly those with comorbid renal impairment, altered hepatic metabolism, or gastrointestinal malabsorption syndromes-is profound and often underestimated. A change in excipients, even if bioequivalence is technically met, can alter dissolution kinetics in ways that are clinically significant but statistically insignificant in trials. The emotional and financial toll on patients who experience adverse events due to unintended substitutions is incalculable. We must advocate for policy reform, pharmacist discretion, and patient autonomy in this domain.

Nnaemeka Kingsley December 3 2025

bro this is wild. i got my cousin on tacrolimus after his transplant and they switched his generic like 3 times in 6 months. he started feeling weak, lost weight, got fever. doc had to admit him. now they just stick with the same brand. why cant they just leave it alone? money ain’t worth life.Kshitij Shah December 4 2025

So let me get this straight: in India, we pay $2 for a month’s supply of generic levothyroxine and everyone’s fine. But in the US, you’re all having panic attacks over a 5% variation? Funny how ‘precision medicine’ becomes a luxury when your insurance won’t cover the brand. Meanwhile, my aunt in Delhi takes the same generic for 12 years-no issues, no labs, just a pill and a prayer. Maybe the problem isn’t the drug. Maybe it’s the over-testing, over-medicalizing culture. Just saying.

Sean McCarthy December 6 2025

This is why we need mandatory blood monitoring for all NTI drug patients. No exceptions. Every single refill. Every single time. No more 'trust the pharmacist.' No more 'it's probably fine.' If you're on warfarin or tacrolimus, you're not a patient-you're a walking lab rat. And if your doctor isn't ordering monthly INR or trough levels, they're negligent. Period.Tommy Walton December 7 2025

It’s not about generics. It’s about ontological insecurity in pharmacology. We’ve outsourced identity to pills-each capsule a metaphysical anchor. When the generic changes, the self destabilizes. The body becomes a site of epistemic rupture. We crave constancy not because of pharmacokinetics-but because we fear meaninglessness. 💫

James Steele December 8 2025

Let’s cut through the regulatory fluff. The FDA’s ‘tightened’ bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs? A PR stunt. The real issue? Manufacturers are using different polymorphs, fillers, and coating technologies that alter dissolution profiles-things bioequivalence studies don’t catch because they’re designed to ignore inter-individual variability. And don’t get me started on the ‘same manufacturer’ myth. That’s just a placebo effect dressed up as science. Real safety? Pharmacogenomic-guided dosing. That’s the only thing that matters. The rest is corporate theater.

Louise Girvan December 10 2025

They’re lying. The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. The ‘same manufacturer’ rule? A trap. They know generics can vary-and they want you to think it’s safe so you don’t sue. Your doctor won’t tell you. Your pharmacist won’t tell you. But I know. I’ve seen the internal memos. Don’t trust ANY generic. Ever.