When a generic drug gets tentative approval from the FDA, it doesn’t mean it’s ready to hit shelves. It means the agency has checked every scientific box - the chemistry, the manufacturing, the bioequivalence - and found it’s just as safe and effective as the brand-name version. But the drug still can’t be sold. Why? Because something else is blocking it. And that something is often not a science problem. It’s a legal, financial, or bureaucratic one.

What Tentative Approval Actually Means

Tentative approval is a regulatory green light that says: "You’ve passed all the tests. You’re ready to go - as soon as the patents expire." It was created under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 to speed up generic access. Instead of waiting until the brand-name drug’s patent runs out to start the review, companies can submit their applications years in advance. The FDA reviews them early. If they’re solid, they get tentative approval. That way, the moment the patent expires, the generic can launch immediately. But in practice, that immediate launch rarely happens. Between 2010 and 2016, nearly 7 out of 10 tentatively approved generics faced delays before hitting the market. Even today, the median time from tentative approval to actual sale is over 16 months. That’s not a glitch. It’s the system working as intended - for someone else.Patent Litigation Is the Biggest Roadblock

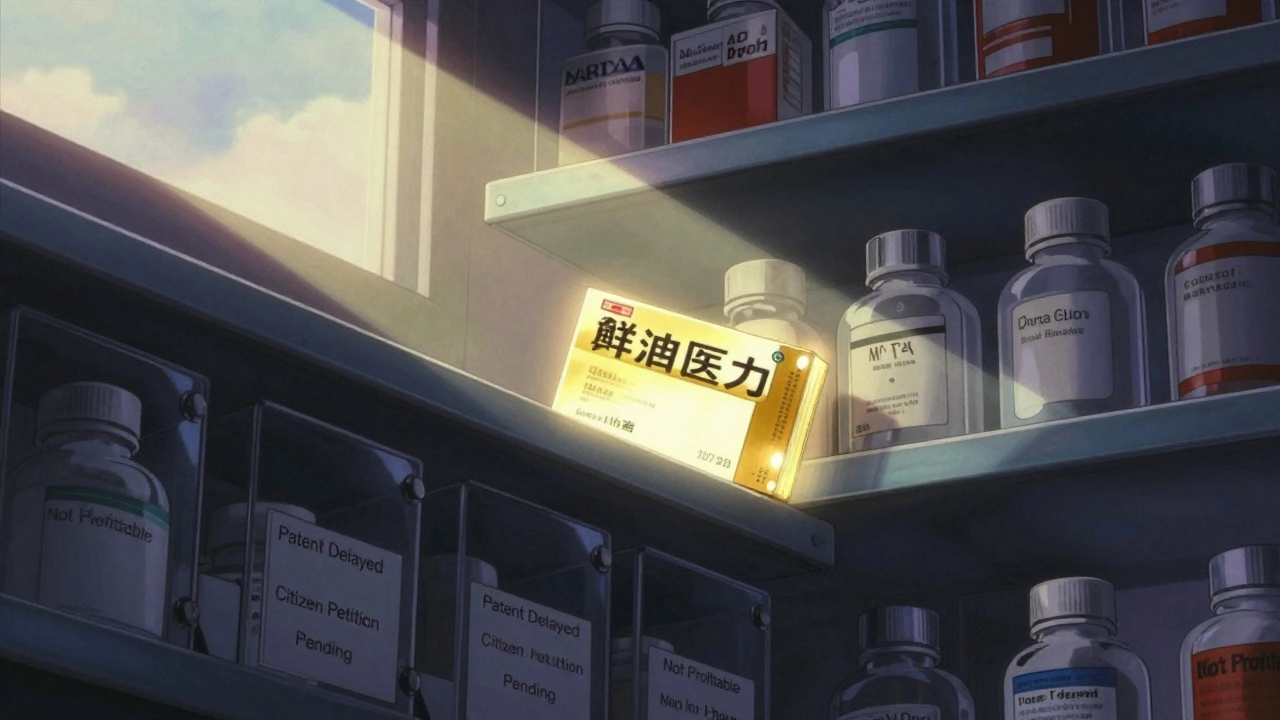

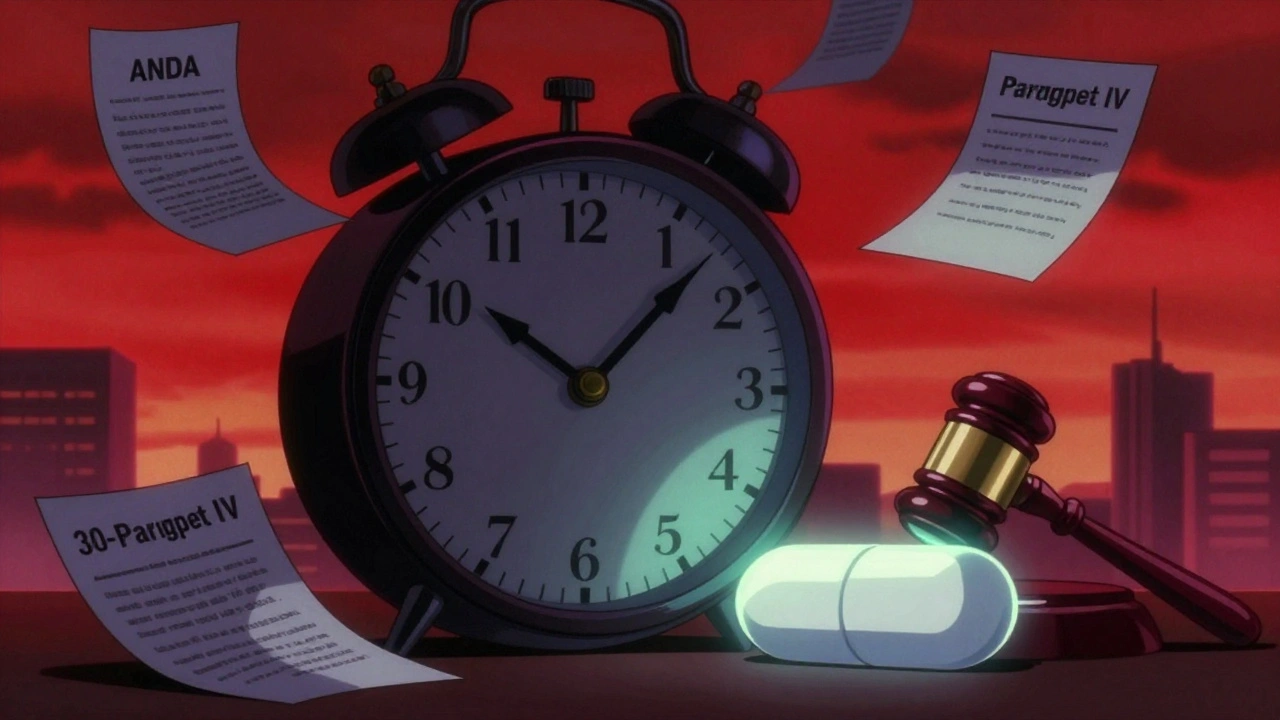

The most common reason a tentatively approved generic doesn’t launch? A lawsuit. When a generic company files an ANDA and says the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed (called a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name company can sue. And when they do, the FDA is legally forced to hold off on final approval for up to 30 months. This isn’t just a delay. It’s a full stop. Even if the FDA has already approved the generic’s quality and safety, the law says: no sale until the court decides. And court cases take time. Some drag on for years. In 2017, the Commonwealth Fund found that 68% of tentatively approved generics were stuck because of these lawsuits. Worse, brand companies often file these lawsuits even when the patent is weak or borderline. Why? Because it buys them time. And time means more profits. In 2015, the FTC reported that between 2009 and 2014, nearly 1,000 generic launches were delayed by "pay-for-delay" deals - where brand companies paid generic makers to stay off the market. These deals cost consumers billions.Citizen Petitions: The Silent Delay Tactic

Another tactic brand companies use? Citizen petitions. These are formal requests to the FDA asking them to delay approval on technical grounds. On paper, they’re meant to raise safety concerns. In practice, many are just legal tools. Between 2013 and 2015, the FDA received 67 citizen petitions targeting generic drugs. Only three were granted. But here’s the catch: even if the FDA denies the petition, the process itself takes months. And while the petition is pending, the FDA can’t issue final approval. A 2017 study found that petitions filed within 30 days of a patent expiration delayed generic entry by an average of 7.2 months. The FDA itself admitted in 2017 that 72% of these petitions from brand companies were based on scientifically unsupported arguments. They’re not about safety. They’re about slowing down competition.

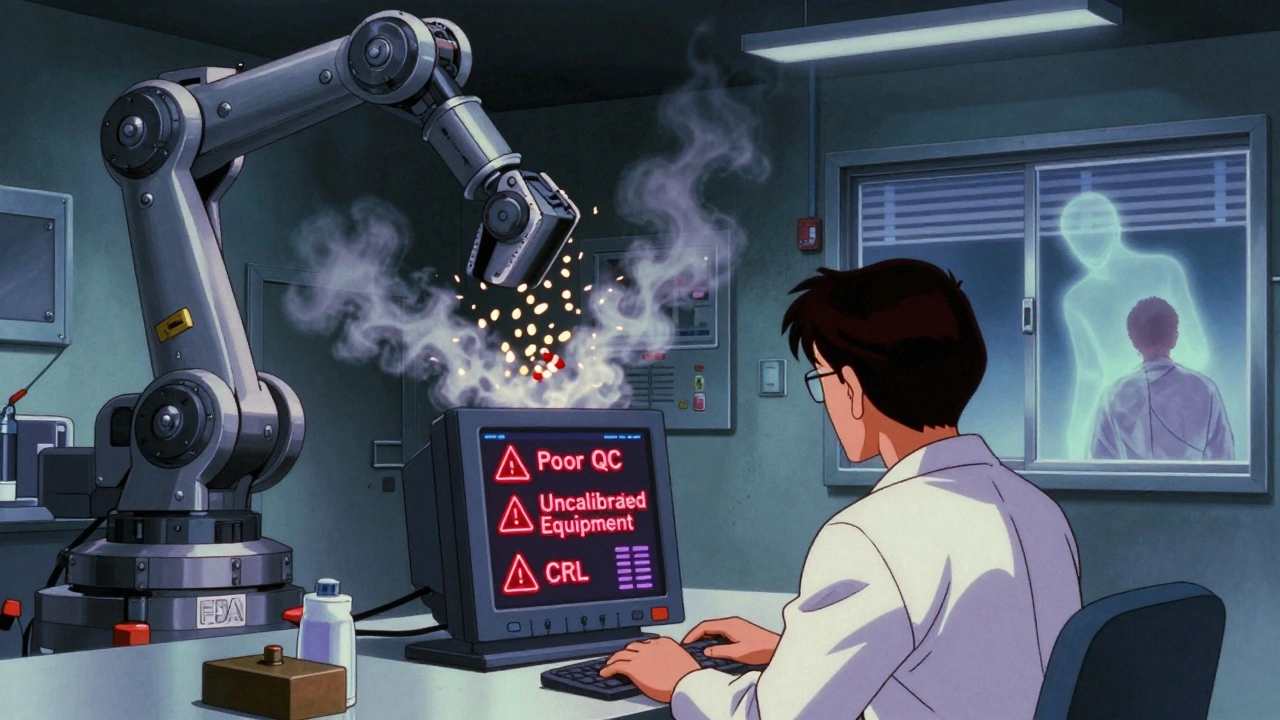

Manufacturing Problems Keep Drugs Off Shelves

Even without lawsuits, many generics never make it to market because the factory can’t make them right. The FDA inspects manufacturing sites before approving a drug. And too often, those inspections turn up problems. In 2022, 41% of complete response letters (CRLs) - the FDA’s official "we can’t approve this yet" notices - were due to facility issues. The most common? Poor quality control systems. That means the company can’t prove every batch of the drug is the same. Or they didn’t properly test the environment where the drug is made. Or their equipment wasn’t calibrated right. These aren’t small fixes. They require retraining staff, redesigning processes, and retesting everything. The average time to respond to a CRL? 9.2 months. The FDA recommends 6. Many companies take longer because they’re underfunded or lack expertise. Complex drugs make this worse. Inhalers, injectables, topical creams - these aren’t simple pills. They’re hard to copy. A 2020 study found that complex generics go through 3.7 review cycles on average, compared to 2.9 for regular pills. That’s 14 extra months of delays.Applications That Aren’t Ready

Sometimes the problem starts before the FDA even looks at the application. A lot of companies submit incomplete or poorly written ANDAs. In 2021, the FDA found that 29% of initial applications had major gaps - missing stability data, unclear labeling, or flawed bioequivalence studies. Stability data? That’s proof the drug won’t break down over time. If it’s missing, the FDA can’t know if the generic will work after six months on a shelf. Container closure systems? That’s the vial or blister pack. If it doesn’t protect the drug from moisture or air, the medicine could go bad. These aren’t obscure details. They’re basic requirements. But many generic companies, especially smaller ones, don’t have the resources to get it right the first time. So they submit, get rejected, and start over. Each cycle adds months.

Market Economics: Why Some Generics Just Don’t Launch

Even if a company clears every hurdle - patents, inspections, paperwork - they might still decide not to launch. Why? Because it doesn’t make financial sense. A 2022 analysis found that 30% of tentatively approved generics never hit the market. For drugs with annual sales under $50 million, that number jumps to 47%. Why? Because the profit margin is too thin. Once multiple generics enter, prices crash. Sometimes to pennies per pill. If the cost to manufacture and distribute the drug is higher than what you can sell it for, you walk away. This is especially true for older drugs with low demand. Companies wait. They watch. They see if another generic enters first. If prices stay high, they launch. If not, they sit on the approval and wait for a better time. That’s why some drugs have tentative approval for years - and still no generic on the shelf.What’s Being Done to Fix It

The FDA knows the system is broken. They’ve tried to fix it. The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) started in 2012 and were renewed in 2023. It gave the FDA more money to hire reviewers and set deadlines. The goal? Reduce review cycles from nearly four to two. So far, they’ve dropped it to 3.2. Still too high. They created the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway for drugs with little or no competition. Those get priority review. About 78% of CGT drugs get tentative approval in under 8 months - half the normal time. In 2022, the FDA picked 102 high-priority tentatively approved drugs with no competition and fast-tracked them. Two-thirds got final approval within a year. That’s better than the 34% average before. But the biggest hurdles - patents, lawsuits, pay-for-delay deals - aren’t in the FDA’s control. Those need Congress to act. The CREATES Act of 2019 tried to stop brand companies from blocking access to samples needed for testing. The Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act of 2023 aims to help U.S. manufacturers build capacity. But enforcement is weak. And lawsuits still fly.What This Means for Patients

The bottom line? Tentative approval doesn’t mean affordable medicine is coming soon. It means the system is working - just not for patients. As of 2020, over 500 brand drugs still had no generic version. Over 300 of them had tentative approvals sitting on a shelf, held up by patents, petitions, or profit calculations. Patients pay the price. In 2018, the Congressional Budget Office estimated patent delays added $9.8 billion to U.S. drug spending. By 2027, that number could hit $12.4 billion. Generics are supposed to cut costs by 80%. But when they’re delayed, prices stay high. And people go without. The science is there. The approvals are there. What’s missing is the will to let them work.What is the difference between tentative approval and final approval for generics?

Tentative approval means the FDA has confirmed the generic drug meets all scientific and manufacturing standards for safety and effectiveness. But final approval can’t be granted until any existing patents or exclusivity periods on the brand-name drug expire. Only then can the generic be legally sold.

Can a generic drug be sold immediately after receiving tentative approval?

No. Tentative approval is not a green light to sell the drug. It’s a holding pattern. The generic manufacturer must wait until all patent protections and regulatory exclusivities on the brand-name drug expire before the FDA can issue final approval and allow sales.

Why do patent lawsuits delay generic drug launches even after tentative approval?

When a generic company challenges a patent (via a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name manufacturer can file a lawsuit. U.S. law automatically triggers a 30-month stay that blocks the FDA from granting final approval - regardless of whether the patent is valid or not. This gives the brand time to litigate and often delays generic entry for years.

How do citizen petitions delay generic approvals?

Citizen petitions are formal requests asking the FDA to take action - like rejecting a generic application. Brand companies often file them to create delays, even when the petition lacks scientific merit. The FDA must respond, and until it does, final approval is paused. On average, petitions filed near patent expiration delay launches by over 7 months.

Why do some tentatively approved generics never reach the market?

Even after clearing all regulatory hurdles, companies sometimes choose not to launch. This often happens with low-revenue drugs where profit margins are too thin after price competition kicks in. For drugs with annual sales under $50 million, nearly half of tentatively approved generics are never launched because it’s not financially viable.

Has the FDA improved the timeline for tentative approvals?

Yes, but slowly. Under GDUFA II, the average number of review cycles dropped from 3.9 to 3.2. The FDA’s Fast-Track initiative for high-priority generics helped 67% of them get final approval within 12 months - up from 34% before. But the median time from tentative to final approval remains over 16 months, and patent delays still dominate the timeline.

Comments (9)

Allan maniero December 2 2025

Man, I’ve been watching this whole generic drug mess for years. It’s wild how the system’s designed to look like it’s working for patients, but really it’s just a legal maze for Big Pharma to stretch profits. I remember when my dad needed that blood pressure med - same active ingredient, same pill, just no generic. Paid $400 a month. Then, three years later, boom - $12. All because some lawyer filed a petition that took 18 months to deny. The FDA’s just a traffic cop with no power to change the road.

It’s not about science anymore. It’s about who owns the paperwork. And patients? We’re just the ones stuck in the waiting room with the receipt for a bill we can’t afford.

Anthony Breakspear December 3 2025

Let’s be real - this isn’t a broken system. It’s a *feature*. The whole ‘tentative approval’ thing is just a shiny sticker on a coffin. Brand companies don’t care if the generic’s safe - they care if it’s *late*. And guess what? Pay-for-delay deals? Those aren’t shady - they’re corporate strategy. The FTC’s been yelling about this since 2010, but Congress? Too busy taking campaign cash from pharma to do anything.

Meanwhile, people are skipping insulin doses because the generic that’s been tentatively approved since 2021 still hasn’t hit shelves. We’re not talking about some niche drug here. We’re talking about life-or-death stuff. And the system? It’s laughing.

PS: The FDA’s ‘fast-track’ for 102 drugs? Cute. That’s like giving a firehose to someone drowning in a bathtub.

Zoe Bray December 3 2025

It is imperative to underscore the structural inefficiencies inherent in the regulatory framework governing Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). The confluence of Paragraph IV certifications, 30-month stays, and non-meritorious citizen petitions constitutes a classic case of regulatory capture, wherein private interests subvert public health objectives.

Furthermore, the persistence of manufacturing deficiencies - particularly in quality control systems and container closure integrity - reflects a systemic underinvestment in cGMP compliance among smaller generic manufacturers. The median time-to-approval of 16 months is not merely a logistical delay; it is a manifestation of institutional inertia and fragmented stakeholder alignment.

While GDUFA II has improved review cycles from 3.9 to 3.2, the absence of legislative intervention regarding patent thickets and pay-for-delay agreements renders these incremental gains largely symbolic.

Eddy Kimani December 5 2025

Wait - so if the FDA says it’s good, why can’t they just approve it? Is there a legal loophole here? Or is this just a loophole they created on purpose? Because if the science checks out, why does a court case override that? It feels like the system’s rigged to make the FDA look like it’s doing its job while actually letting pharma call the shots.

And what’s up with citizen petitions? Like, I get that you can petition the government, but if 72% of them are scientifically baseless, why isn’t there a penalty? Why not charge companies for wasting agency time? That’s like filing a false police report and getting a pat on the head.

Also - why do some companies just not launch? Isn’t that like having a winning lottery ticket and deciding not to cash it because the prize is too small? That’s not rational. That’s… sad.

John Biesecker December 6 2025

so like… the system is basically saying "you passed the test, but nope, not yet" 😭

imagine studying for a year for your driver’s license, passing every exam, getting your certificate… then someone says "lol nope, we’re waiting for the car company to finish their lawsuit with the other car company"

and then you find out they’re just doing it to keep prices high 😤

also why do we even have citizen petitions if they’re just being used as delay tactics? this is like giving someone a remote control to pause your life for 7 months. i’m not mad… i’m just disappointed.

also i cried reading this. not because i’m weak. because this is real. people are dying because of paperwork. 🥺

Genesis Rubi December 6 2025

USA invented this system. We don’t need some Indian or Chinese factory making our meds. Why are we letting foreign manufacturers get approved while our own factories go bankrupt? This isn’t about science - it’s about sovereignty. We’re letting the world walk all over our healthcare. And now we’re paying more because some lawyer in New York decided to drag his feet for 3 years? Pathetic.

Also, if you can’t make a pill right, you shouldn’t be in business. That’s not a "manufacturing problem" - that’s incompetence. Fix your own damn factories. Stop outsourcing and then crying when it’s slow.

Doug Hawk December 7 2025

One thing no one talks about is how the FDA’s inspection backlog is tied to funding. They’ve got the authority, but not the staff. Every CRL for facility issues? That’s not the company being sloppy - it’s the FDA not having enough inspectors to catch it early. So they wait until the end, then say "nope, fix this."

And the citizen petitions? Yeah, they’re abuse. But the FDA has to respond. No choice. It’s a loophole in the law, not a flaw in the agency. Congress wrote this. The FDA just has to follow it.

Also - the 30-month stay? That’s not a delay. That’s a statutory requirement. If you want to change it, you need a new law. Not a tweet. Not a rant. A bill. With votes.

It’s not the FDA’s fault. It’s the system. And the system is broken by design.

Carolyn Woodard December 7 2025

It’s chilling how the language of science - bioequivalence, stability data, cGMP - gets weaponized to serve economic interests. The FDA’s role has been reduced from gatekeeper of public health to administrative clerk for litigation. Tentative approval is a bureaucratic mirage: a promise that looks like progress but is structurally incapable of delivery.

And yet, the most tragic layer is the silent calculus of market withdrawal - where companies, faced with the inevitability of price collapse, choose not to launch. Not because they can’t - because they won’t. The market, in this context, doesn’t reward access. It rewards restraint.

There is no technical fix for this. Only moral and legislative courage. And so far, we’ve chosen silence.

Saket Modi December 9 2025

bro this is why i hate america. so much red tape for nothing. just let the pills sell already 😒