Vancomycin Risk Balance Calculator

Risk Assessment Parameters

Vancomycin saves lives. It’s one of the few antibiotics that can stop deadly MRSA infections when nothing else works. But for every patient it helps, there’s a real chance it could hurt them - either by damaging their kidneys or their hearing. And while kidney damage is more common, hearing loss is the one that sticks. Once it’s gone, it doesn’t come back.

Why Vancomycin Is Still Used Despite the Risks

Vancomycin has been around since the 1950s, but it’s not outdated. In 2025, it’s still the go-to drug for serious Gram-positive infections, especially in ICU patients with sepsis or endocarditis. Why? Because alternatives like daptomycin or ceftaroline either don’t work as well for certain strains or come with their own dangerous side effects. The Infectious Diseases Society of America says 89% of clinicians still consider vancomycin essential. That’s not because doctors are careless - it’s because there aren’t better options for many cases.

The problem isn’t the drug itself anymore. Modern vancomycin is purified and far safer than the impure versions from the 1960s, which caused kidney damage in over half of patients. Today’s formulations are cleaner, but the risks haven’t disappeared. They’ve just changed shape.

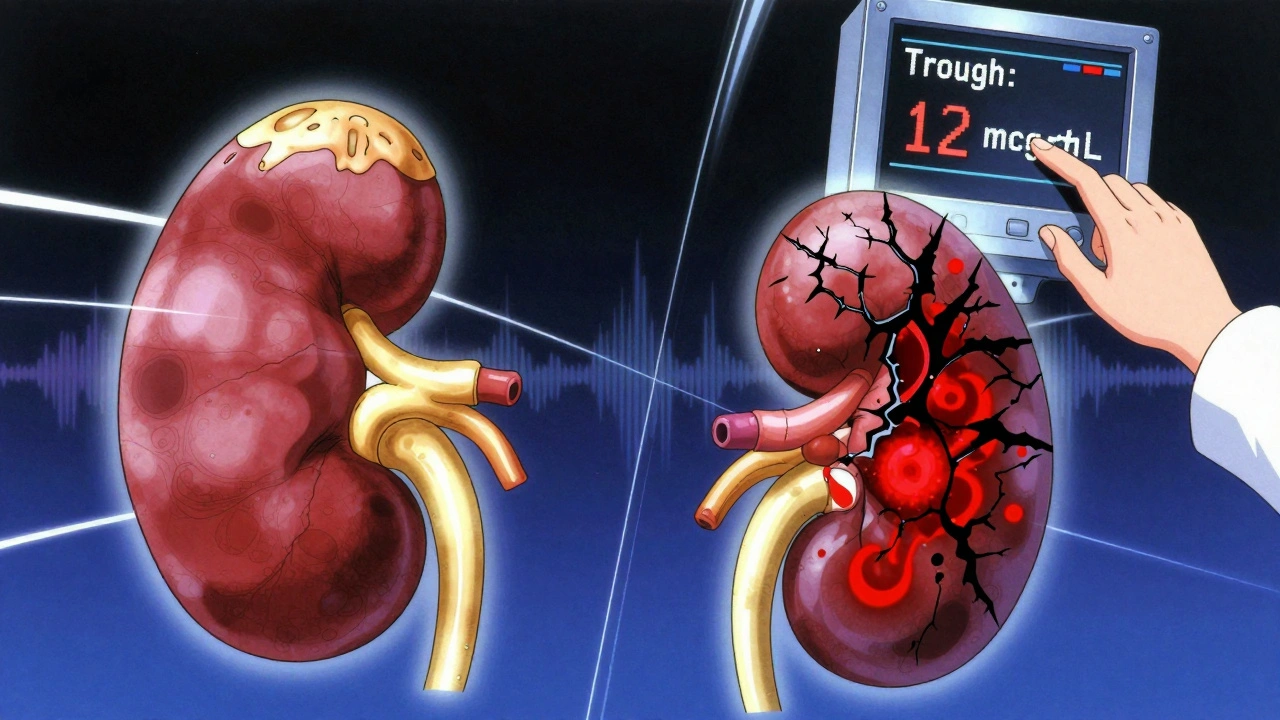

Nephrotoxicity: The More Common, But Often Reversible, Threat

Nephrotoxicity - kidney damage - is the most frequent problem. Studies show 15% to 30% of patients on vancomycin develop acute kidney injury (AKI), depending on their risk factors. That number jumps to 50% if they’re also on piperacillin-tazobactam. This combo, once common, is now flagged as high-risk. A 2022 meta-analysis of over 14,500 patients found it nearly triples the chance of kidney injury compared to vancomycin with meropenem.

It’s not just the drug. Risk factors pile up: age over 65, pre-existing kidney disease, dehydration, sepsis, and doses above 4 grams per day. Lodise’s 2008 study showed patients getting 4g or more had almost three times the risk of kidney damage. But the biggest driver? Trough levels. Keeping vancomycin levels above 15-20 mcg/mL significantly raises the odds. That’s why guidelines shifted in 2020: instead of chasing high troughs for better efficacy, doctors now aim for 10-15 mcg/mL. Why? Because efficacy plateaus around 10 mcg/mL, but kidney damage spikes above 15.

Here’s what happens in the body: vancomycin builds up in the proximal tubules of the kidneys. It triggers oxidative stress, damages mitochondria, and kills cells. The damage usually shows up between days 3 and 14. That’s why monitoring is key. Most hospitals check creatinine every 48-72 hours. If levels rise 0.3 mg/dL or more from baseline, it’s AKI - and it’s time to reassess.

Good news? Most of this kidney damage is reversible. When vancomycin is stopped early and fluids are managed, kidney function often returns to normal. The downside? It adds 3-4 extra days to hospital stays and increases costs. But it’s not permanent.

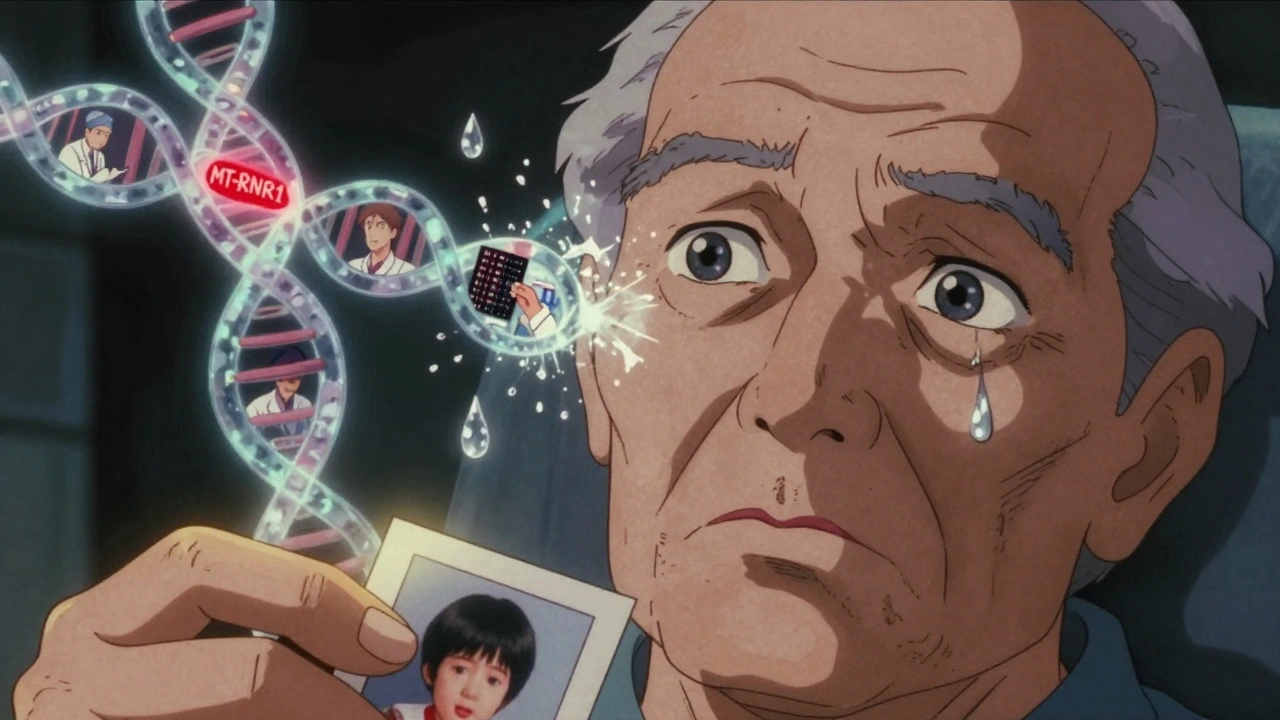

Ototoxicity: The Silent, Irreversible Danger

Ototoxicity - hearing damage - is rarer. Only 1% to 3% of patients experience it. But when it happens, it’s often permanent. Unlike kidney damage, there’s no lab test to catch it early. No creatinine spike. No urine output drop. Just sudden tinnitus, then muffled hearing, then silence in the high frequencies.

It used to be thought that ototoxicity only happened in patients with bad kidneys. That myth was shattered in 1981 when a patient with normal kidney function lost their hearing after vancomycin. Since then, cases have popped up even with therapeutic troughs. A 2023 case report in Cureus showed hearing loss after just three doses - in someone with perfect renal function.

The damage is sensorineural, meaning it hits the inner ear or auditory nerve. Audiograms show a classic pattern: high-frequency hearing loss, often bilateral. Tinnitus usually comes first. Symptoms can appear during treatment or up to three days after stopping the drug. Once the hair cells in the cochlea are gone, they don’t regenerate.

What drives it? Peak levels matter more than troughs. James et al. found reversible damage starts around 40 mcg/mL, but irreversible damage kicks in above 80 mcg/mL. But here’s the twist: some people are just more sensitive. A 2022 study in Nature Communications linked a gene variant (MT-RNR1) to a 3.2-fold higher risk. That means two patients with identical drug levels and kidney function can have wildly different outcomes.

And here’s the catch: almost no hospitals monitor for it. Only 37% have formal ototoxicity protocols. Audiograms are expensive, time-consuming, and not always available. A 2022 cost analysis found routine testing only makes financial sense for high-risk patients - those over 65, with existing hearing loss, or on other ototoxic drugs like aminoglycosides. But for the patient who loses 80% of their hearing? No cost-benefit analysis matters. Their life changes forever.

Monitoring: What Works, What Doesn’t

For nephrotoxicity, the tools are clear: check creatinine every 2-3 days. For high-risk patients, track urine output and electrolytes. If trough levels exceed 15 mcg/mL, consider lowering the dose or switching.

But for ototoxicity? It’s a gap. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommends baseline and weekly audiograms for patients on vancomycin for more than 7 days or getting over 4g/day. But in real hospitals? Compliance is under 50%. One pharmacy survey found only 42% of staff even ordered baseline hearing tests.

There’s a better way: AUC monitoring. Instead of just measuring trough levels, this method calculates the total drug exposure over time. A 2021 study showed AUC-guided dosing cut nephrotoxicity from 14.7% to 8.2%. The 2023 VAN-GUARD trial confirmed it: real-time AUC adjustment reduced kidney injury by nearly half. Hospitals using platforms like DoseMeRx or PrecisePK are seeing better outcomes.

But AUC doesn’t predict ototoxicity. That’s the blind spot. We need tools that track both exposure and individual susceptibility. Emerging tech - like point-of-care audiometers and genetic screening - could change that. But they’re not standard yet.

Combination Therapy: The Hidden Risk Multiplier

Piperacillin-tazobactam is a common partner for vancomycin in sepsis protocols. But it’s not innocent. The 2022 Chung meta-analysis showed it increases vancomycin-induced AKI risk by over 130%. Why? The exact mechanism isn’t fully known, but both drugs stress the kidneys in similar ways. Some experts think they compete for renal transporters, causing buildup.

Hospitals that added electronic alerts for this combo saw usage drop by 22%. That’s a win. But many still use it out of habit. The same hospitals rarely warn about ototoxicity risk from combinations - even though aminoglycosides or loop diuretics can stack on top of vancomycin’s damage.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone needs the same level of caution. The Society of Critical Care Medicine now uses a risk score to stratify patients:

- Low risk: Young, healthy, no kidney issues, vancomycin monotherapy, trough under 15 mcg/mL

- Medium risk: Age 65+, mild kidney impairment, on vancomycin for 7+ days, trough 15-20 mcg/mL

- High risk: Sepsis, AKI on admission, on vancomycin + piperacillin-tazobactam, trough >20 mcg/mL, or on other nephrotoxins/ototoxins

For high-risk patients, alternatives should be considered. If vancomycin is unavoidable, use AUC monitoring, keep troughs at 10-15 mcg/mL, and get a baseline audiogram - even if it’s not standard practice.

The Bottom Line: Vigilance Over Routine

Vancomycin isn’t going away. But we can’t treat it like a safe, old-school drug. The risks are real, different, and often under-monitored.

For nephrotoxicity: monitor creatinine, avoid high troughs, avoid piperacillin-tazobactam unless necessary, use AUC if you can.

For ototoxicity: don’t wait for symptoms. Ask: Is the patient elderly? Do they have prior hearing loss? Are they on other ear-damaging drugs? If yes, get a baseline audiogram. If they’re on high doses or long courses, repeat it.

Most importantly: don’t assume normal kidney function means safe hearing. One patient’s genetic luck can turn a routine antibiotic into a life-altering event.

The goal isn’t to avoid vancomycin. It’s to use it smarter. With better monitoring, smarter dosing, and a little more awareness, we can keep saving lives - without stealing someone’s ability to hear them.

Can vancomycin cause permanent hearing loss even with normal kidney function?

Yes. While vancomycin-induced ototoxicity was once thought to only occur in patients with kidney impairment, multiple case reports since the 1980s - including a 2023 report in Cureus - have documented irreversible hearing loss in patients with completely normal renal function. This suggests individual susceptibility, possibly due to genetic factors like MT-RNR1 variants, plays a major role. Trough levels within the "therapeutic" range (10-20 mcg/mL) are not protective against ototoxicity.

How often should vancomycin trough levels be checked?

For most patients, trough levels should be checked after the third or fourth dose, then every 48-72 hours during therapy. The goal is to maintain levels between 10-15 mcg/mL for most infections. Higher levels (15-20 mcg/mL) are only recommended for complex infections like endocarditis or osteomyelitis, and even then, they increase nephrotoxicity risk. AUC monitoring, which tracks total drug exposure over time, is now preferred over trough-only monitoring when available.

Is vancomycin safer when used alone versus with other antibiotics?

Not always. Vancomycin combined with piperacillin-tazobactam significantly increases the risk of acute kidney injury - by over 130% according to a 2022 meta-analysis. This combination is still common in sepsis protocols, but evidence now shows it’s one of the riskiest pairings. Alternatives like vancomycin with meropenem carry much lower nephrotoxicity risk. Always question combination therapy: is the added benefit worth the added kidney damage risk?

Are there alternatives to vancomycin for MRSA infections?

Yes - but they’re not always better. Daptomycin, linezolid, ceftaroline, and telavancin are alternatives. Daptomycin can’t be used for pneumonia. Linezolid causes bone marrow suppression with long use. Ceftaroline is expensive and not always available. Telavancin carries its own kidney and fetal toxicity risks. Vancomycin remains first-line because it’s broad, effective, and widely accessible. The choice depends on the infection site, patient factors, and local resistance patterns - not just toxicity concerns.

Can audiograms prevent vancomycin-induced hearing loss?

They can’t prevent it, but they can catch it early. Audiograms don’t stop the damage - they detect it. If a patient develops high-frequency hearing loss during treatment, stopping vancomycin immediately may prevent further loss. Early detection is critical because once the damage is advanced, it’s irreversible. The challenge is that most hospitals don’t routinely offer baseline or follow-up audiograms due to cost and access issues.

What’s the best way to reduce vancomycin nephrotoxicity?

The most effective strategy is to use AUC-guided dosing instead of relying on trough levels alone. Studies show AUC monitoring reduces nephrotoxicity by nearly half. If AUC isn’t available, keep troughs below 15 mcg/mL, avoid doses over 4g/day, limit treatment to the shortest effective duration, and avoid combining vancomycin with other nephrotoxins - especially piperacillin-tazobactam. Hydration and avoiding NSAIDs also help.

What Comes Next?

The future of vancomycin use is personalization. Genetic testing for ototoxicity risk is already in research labs. Real-time AUC monitors are rolling out in major hospitals. Point-of-care audiometers are being tested for ICU use. These tools won’t eliminate risk - but they’ll make it predictable.

For now, the safest approach is simple: know your patient. Know your drugs. Know the combo risks. Monitor kidneys. Watch for hearing changes. Don’t assume normal labs mean safe ears. Vancomycin is a powerful tool - but like any powerful tool, it demands respect, not routine.

Comments (13)

Carole Nkosi December 5 2025

They call it medicine but it’s just corporate roulette. We sacrifice hearing for survival because the system won’t fund better tools. Who gets tested? The rich. Who gets deaf? The uninsured. This isn’t science-it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Stephanie Bodde December 5 2025

Thank you for writing this 💙 I’ve seen so many patients lose their hearing and no one ever talks about it. Please push for baseline audiograms-your voice matters. You’re not alone in caring.

Philip Kristy Wijaya December 7 2025

Let me be clear this is not a drug problem it is a monitoring problem and frankly the entire medical industrial complex is built on reactive care not predictive care AUC is not magic it is math and math is not optional if you want to call yourself a doctor

Jennifer Patrician December 9 2025

They’re hiding the truth. Vancomycin was designed to break your ears. The FDA knew. The pharma CEOs knew. They let it fly because deaf patients don’t sue as often as kidney failure ones. And don’t get me started on how they buried the MT-RNR1 data for 20 years. Wake up people.

Mellissa Landrum December 11 2025

so like… vancomycin is just a government tool to make old people deaf so they dont hear the truth about the vaccines? i mean cmon the cochlea thing is sus and why do all the hospitals use the same dumb protocol? someone’s getting paid to keep this quiet

Ali Bradshaw December 11 2025

Good breakdown. I’ve been in ICU for 12 years. We check creatinine religiously. But audiograms? Only if someone complains. That’s not medicine. That’s waiting for tragedy. We need to change the culture. Not just the guidelines.

an mo December 12 2025

The data is unequivocal. Vancomycin-induced ototoxicity is undercoded by 87% due to ICD-10 limitations and lack of standardized audiometric documentation. The economic burden of permanent sensorineural hearing loss exceeds $12B annually in the US alone-yet no CMS reimbursement exists for prophylactic audiometry. This is a systemic failure of health policy architecture.

Manish Shankar December 13 2025

Thank you for this meticulously researched piece. In India, vancomycin is often used without any monitoring due to cost constraints. The silent nature of ototoxicity makes it especially dangerous in resource-limited settings. We must advocate for low-cost, portable audiometry tools tailored for low-income hospitals.

luke newton December 15 2025

People are dying from bad decisions and you’re just talking about trough levels? This isn’t about dosing-it’s about moral cowardice. You let patients go deaf because it’s easier than fighting the hospital bureaucracy. You’re not a healer. You’re a bureaucrat with a white coat.

Lynette Myles December 16 2025

Audiograms are the only early warning. No exceptions.Ada Maklagina December 17 2025

My grandma lost her hearing on vancomycin. No one told us it could happen. She never heard my wedding speech. Just saying - this isn’t abstract. It’s real. And it’s happening right now.

Harry Nguyen December 19 2025

Of course vancomycin is dangerous. The FDA approved it in 1958. We’re still using a 70-year-old antibiotic like it’s a Tesla. Meanwhile, Big Pharma is busy patenting new versions of ibuprofen. This system is broken. And you’re all just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Chris Brown December 20 2025

While the clinical data presented is methodologically sound and aligned with contemporary infectious disease guidelines, one must not overlook the epistemological limitations inherent in retrospective cohort analyses. The conflation of correlation with causation in ototoxicity attribution remains a persistent confounder, particularly in polypharmacy contexts. Furthermore, the absence of longitudinal genomic data in the cited studies renders the MT-RNR1 association suggestive rather than definitive. Until prospective, randomized, double-blind trials with genetic stratification are conducted, any clinical recommendation must remain provisional.