When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way-even though the ingredients are identical? For many people, the difference isn’t in the pill. It’s in their genes. And their family history.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

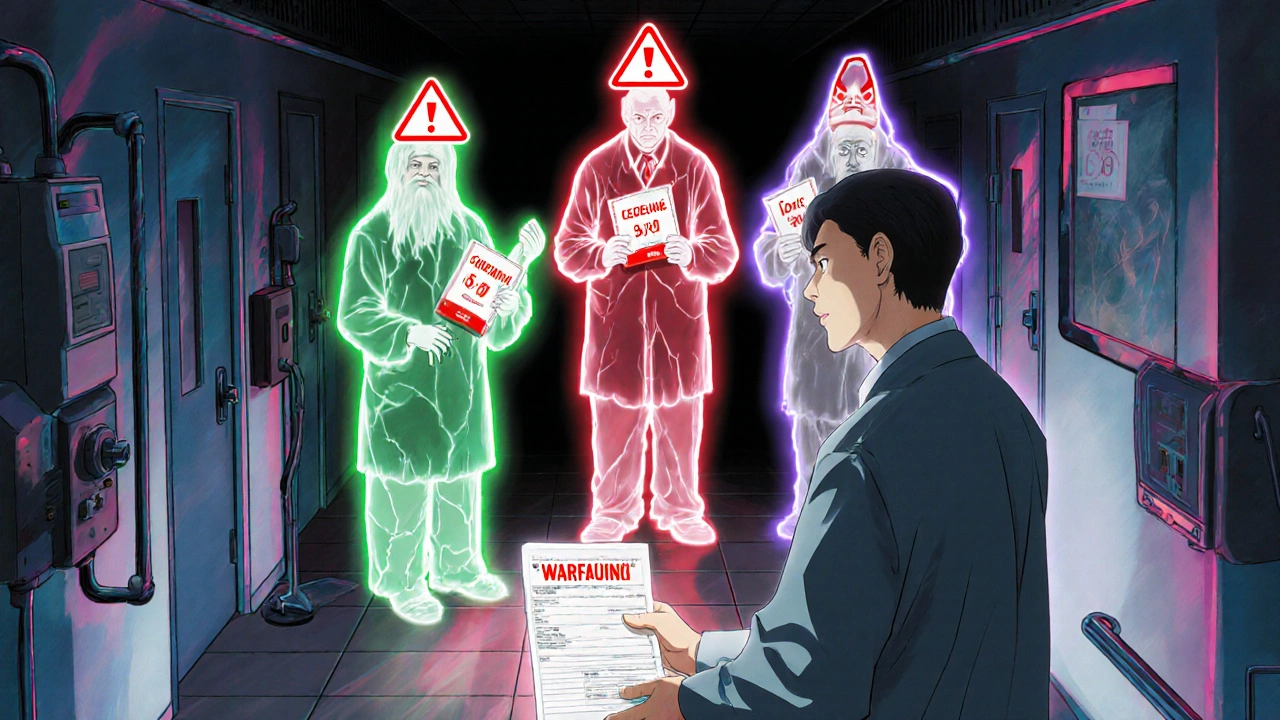

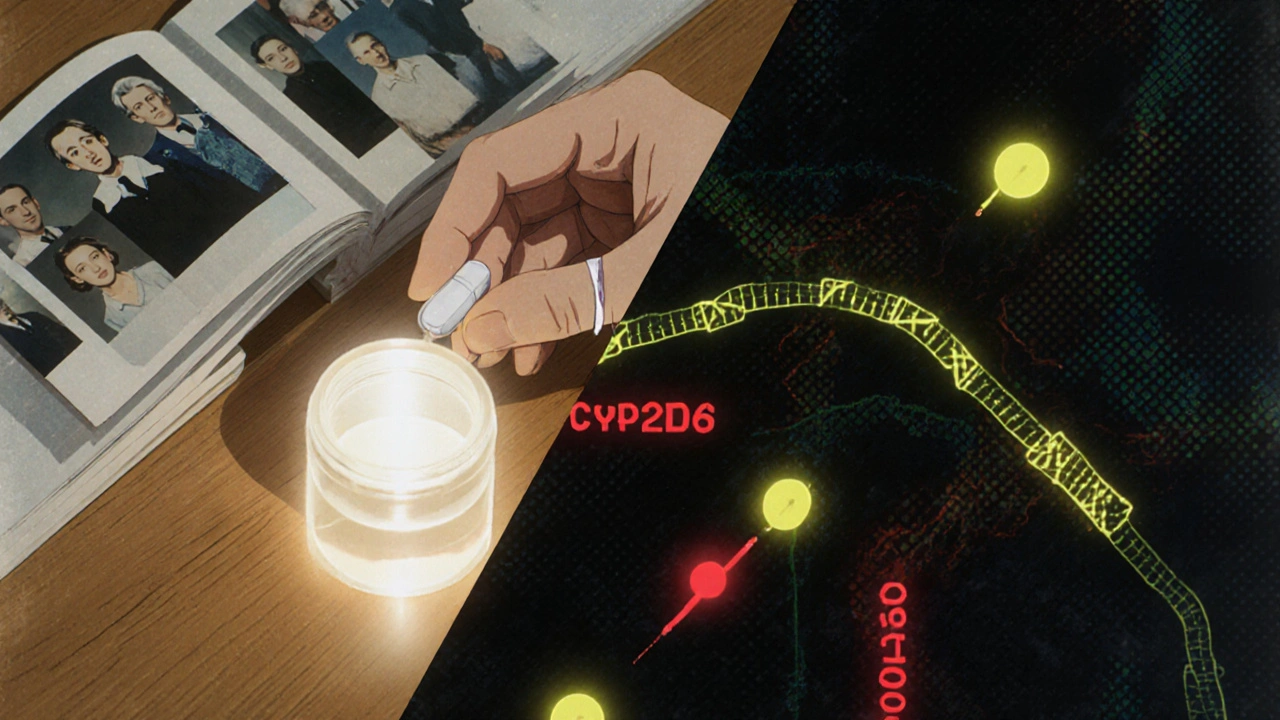

Generic drugs are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts. They have the same active ingredient, dosage, and intended effect. But they don’t always work the same way in every person. Why? Because your body processes drugs based on your unique genetic makeup. This field is called pharmacogenetics-the study of how genes affect how you respond to medications. Genetic variations can make you a fast, slow, or normal metabolizer of drugs. For example, the CYP2D6 gene controls how your liver breaks down about 25% of all prescription medications, including common antidepressants like sertraline and painkillers like codeine. If you inherit two copies of a slow-metabolizer variant, you might build up toxic levels of the drug. If you’re a fast metabolizer, the drug might not work at all. These differences aren’t random. They run in families. If your parent had a bad reaction to a generic version of a drug, or if they needed a higher dose to feel relief, you might share that same genetic profile. It’s not about allergies or tolerance. It’s about biology passed down from generation to generation.Real Examples: When Genetics Change Everything

Take warfarin, a blood thinner often prescribed after a stroke or heart surgery. For decades, doctors used a one-size-fits-all starting dose. Then researchers found that two genes-CYP2C9 and VKORC1-determine how much warfarin a person needs. People with certain variants in these genes can bleed dangerously on standard doses. Others need nearly double the dose to be protected from clots. In the U.S., over 300 drug labels now include pharmacogenetic information from the FDA. Warfarin’s label was updated in 2008 to suggest genetic testing. Today, hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have programs that test patients before prescribing. One study of 10,000 patients found that 42% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. Of those, 67% had their medication adjusted-and adverse events dropped by 34%. Another example is 5-fluorouracil, a chemotherapy drug. A variant in the DPYD gene can cause life-threatening toxicity. Without testing, patients might receive a lethal dose. But if a family member had a severe reaction to this drug, genetic screening before treatment could have saved their life. Even common drugs like proton pump inhibitors (for heartburn) are affected. About 15-20% of Asians are poor metabolizers of these drugs due to CYP2C19 variants. They might need a different medication entirely-even if the generic version is technically identical to the brand.

Family History Isn’t Just a Story-It’s a Clue

When you walk into a doctor’s office and say, “My mom couldn’t take this drug,” that’s not just family gossip. It’s clinical data. Studies show that knowing your family’s drug reactions can predict your own risk of side effects better than age, weight, or even kidney function in some cases. If your father had a dangerous reaction to a generic statin, you might carry the same HMGCR gene variant linked to reduced drug effectiveness. If your sister developed severe skin rashes after taking carbamazepine, you could be at risk for the HLA-B*15:02 variant-which can trigger Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a deadly skin condition. Many doctors still don’t ask these questions. But if you’ve had unexplained side effects, or if your medication stopped working out of nowhere, your family history might be the missing piece. Don’t assume it’s “just how your body is.” Ask: Has anyone else in my family had this problem?Why Some People Get Tested-and Others Don’t

Genetic testing for drug response isn’t new. But it’s still not routine. In the U.S., academic hospitals have been offering preemptive testing for years. Mayo Clinic’s RIGHT program has tested over 167,000 patients. Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program has been running since 2010. Both found that 10-12% of patients had actionable results-meaning their medication needed to be changed before harm occurred. But outside of big hospitals, it’s rare. Only 32% of community hospitals offer any kind of pharmacogenetic testing. Why? Cost, time, and lack of training. A 2022 survey of 1,247 clinicians found that 79% said they didn’t have time to interpret test results. Many didn’t know how to read star allele notation (like CYP2D6*4/*5). Others didn’t trust the guidelines. One patient on Drugs.com wrote: “I paid $350 for a GeneSight test. It said I was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. My psychiatrist ignored it. I ended up in the ER with serotonin syndrome.” The good news? Costs are dropping. Tests from Color Genomics or OneOme now cost under $250. Some insurance plans, including Medicare, cover them for certain drugs. And the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has published 24 clear, evidence-based guidelines for doctors on how to act on results.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need a lab test to start using your family history. Here’s what to do:- Write down every drug your parents, siblings, or grandparents took-and what happened. Did they get sick? Did it not work? Did they need a different dose?

- Bring this list to your next appointment. Say: “I’ve noticed my family has bad reactions to these drugs. Could my genes be involved?”

- If you’re starting a new medication, especially one with known genetic links (like warfarin, clopidogrel, SSRIs, or chemotherapy), ask: “Is there a genetic test I should consider before taking this?”

- If you’ve had unexplained side effects in the past, request a copy of your medical records. Look for terms like “metabolizer status,” “CYP2D6,” or “pharmacogenetic.”

- Codeine: Poor metabolizers get no pain relief. Ultra-rapid metabolizers can turn it into morphine too fast-leading to overdose.

- Thiopurines (used for leukemia and autoimmune diseases): TPMT gene testing prevents life-threatening drops in white blood cells.

- Plavix (clopidogrel): CYP2C19 poor metabolizers get almost no benefit from the drug, raising stroke risk.

The Future Is Personalized-Even for Generics

The idea that one generic drug fits everyone is outdated. We’re moving toward a system where your genetic profile determines your starting dose-even for the cheapest pills on the shelf. The NIH spent $127 million on pharmacogenomics research in 2023. The All of Us program plans to return genetic results to 1 million Americans by 2026. New tools are being developed to predict drug response using hundreds of genes at once-not just one or two. By 2025, 92% of academic medical centers plan to expand their pharmacogenomic programs. The goal isn’t to replace generics. It’s to make them safer and more effective for everyone. If you’re switching to a generic drug because of cost, don’t assume safety comes with the lower price tag. Your genes don’t care about the brand name. They care about your DNA. And that’s something you can-and should-know.Can my family history really predict how I’ll react to generic drugs?

Yes. If close relatives had severe side effects, no response, or unusual dosing needs with a drug, you may share the same genetic variants. Studies show family history is a strong predictor of drug metabolism issues-especially for medications processed by CYP2D6, CYP2C9, or TPMT genes.

Are genetic tests for drug response covered by insurance?

Some are. Medicare covers certain pharmacogenomic tests under its Molecular Diagnostic Services Program, especially for drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, and certain chemotherapies. Private insurers vary, but many cover tests if ordered by a specialist or if there’s a clear clinical reason. Tests from companies like Color Genomics or OneOme cost $249-$499, and some employers offer them as part of wellness programs.

Do I need to get tested before every new prescription?

No. Preemptive testing-getting tested once and keeping the results on file-is the most efficient approach. If you’ve been tested for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, or TPMT, those results apply to all future medications metabolized by those enzymes. Many clinics store your results in your electronic health record so doctors see them automatically.

What if my doctor doesn’t believe in genetic testing?

Ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist or pharmacogenetics specialist. Many hospitals have them. You can also bring printed CPIC guidelines (available online) to your appointment. The guidelines are peer-reviewed and used by top medical centers. If your doctor refuses to consider genetic data, consider switching to a provider who does.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Yes, through direct-to-consumer companies like Color Genomics or 23andMe (which includes some pharmacogenetic markers). But interpreting the results without medical guidance can be risky. A negative result doesn’t mean you’re safe-some variants aren’t tested. Always discuss results with a healthcare provider before changing your medication.

Comments (9)

Javier Rain November 21 2025

I switched to a generic version of sertraline last year and felt like a zombie for three weeks. Then I remembered my mom had the same thing happen-she called it ‘the zombie pills.’ Turned out we’re both CYP2D6 slow metabolizers. Got tested, switched back to brand, and now I’m actually functional again. Family history isn’t gossip-it’s your body’s warning system.

Stop assuming generics are ‘the same.’ They’re chemically identical, but your DNA doesn’t care about the label.

Laurie Sala November 23 2025

OMG, YES!!! I had to go to the ER because my generic carbamazepine gave me Stevens-Johnson syndrome-my sister had it too, but no one ever asked if it ran in the family!!! Why do doctors ignore this?!? I told my PCP for YEARS, and she said, ‘It’s just a coincidence.’ COINCIDENCE?!? My DNA is not a coincidence!!!

Lisa Detanna November 25 2025

As someone raised in a household where ‘medications are magic pills’ and asking questions was seen as disrespectful, I didn’t even know to ask about family reactions until I was 32. My mom took warfarin for years without issues-until she started bleeding internally. Turns out, she had a rare VKORC1 variant. I got tested after that. I’m a fast metabolizer. I take double the dose of my blood thinner, and my doctor finally listened.

It’s not just about you. It’s about your whole lineage. Your ancestors’ reactions are coded in you. Don’t let medical arrogance erase that.

Demi-Louise Brown November 26 2025

The clinical evidence supporting pharmacogenetic testing is robust and well-documented by CPIC and the FDA. The integration of genetic data into prescribing protocols reduces adverse drug events by up to 34%, as cited in peer-reviewed studies from Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt. While cost and provider education remain barriers, preemptive testing offers long-term cost savings and improved patient outcomes. Patients should be encouraged to request testing when initiating medications with known genetic interactions, such as clopidogrel, warfarin, or SSRIs. Medical professionals must prioritize this data as part of standard care.

Generic drugs are not inferior-they are underutilized due to a lack of personalized dosing protocols.

Matthew Mahar November 28 2025

bro i got my 23andme results and it said i’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer… so i took codeine once for a toothache and i felt like i’d been injected with pure adrenaline for 12 hours. i thought i was having a heart attack. my doc laughed and said ‘must’ve been anxiety.’ i almost died. my uncle died from the same thing. i’m never trusting a generic painkiller again. why is this not common knowledge???

Manjistha Roy November 28 2025

My mother was prescribed thiopurines for Crohn’s and nearly died from bone marrow suppression. We didn’t know about TPMT testing until years later. Now I get tested before any new medication. I’m from India, and we have a high rate of TPMT variants-yet no one in my hometown hospital even mentions it. If you’re South Asian, be extra careful with azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or 6-MP. This isn’t theoretical. It’s survival.

Charmaine Barcelon November 29 2025

Ugh. I’m so tired of people acting like this is some new discovery. My grandma died from a bad reaction to a generic statin in 1998. My aunt got hospitalized for serotonin syndrome from a generic SSRI in 2005. We’ve been screaming about this for decades. Doctors still act like it’s a conspiracy theory. It’s not. It’s biology. And they’re too lazy to learn it.

Karla Morales November 30 2025

📊 Data point: 79% of clinicians admit they don’t have time to interpret pharmacogenetic results. 📉 67% of patients with actionable results had their meds adjusted-and adverse events dropped by 34%. 💡 So… we’re prioritizing efficiency over safety? 🤔

Let’s be real: this isn’t about cost. It’s about institutional inertia. Hospitals profit from ER visits. They don’t profit from preventing them. 🧬 The system is designed to react-not to predict.

And yes, I’m a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer. Took me 3 years and 2 failed antidepressants to get tested. Now I take escitalopram instead of sertraline. I’m alive. 💪

Ragini Sharma December 2 2025

my doc told me my generic fluoxetine wasn't working because i was 'noncompliant'... i took it every day. then i found out my dad had the same issue and got switched to a different drug after genetic testing. i asked my doc if i could get tested. she said 'why waste money?'... so i paid out of pocket. turns out i'm CYP2C19 poor. my doc still hasn't changed my script. i'm just waiting to crash again. 🤷♀️