For someone who has lived for years without hearing a child’s laugh, a bird’s song, or even their own voice, the idea of regaining sound isn’t just medical-it’s deeply human. Cochlear implants don’t just improve hearing; they rebuild connection. Unlike hearing aids that make sounds louder, cochlear implants bypass damaged parts of the ear entirely and send electrical signals straight to the auditory nerve. This makes them the only viable option for people with profound sensorineural hearing loss-those who get little to no benefit from traditional hearing aids.

How Cochlear Implants Work

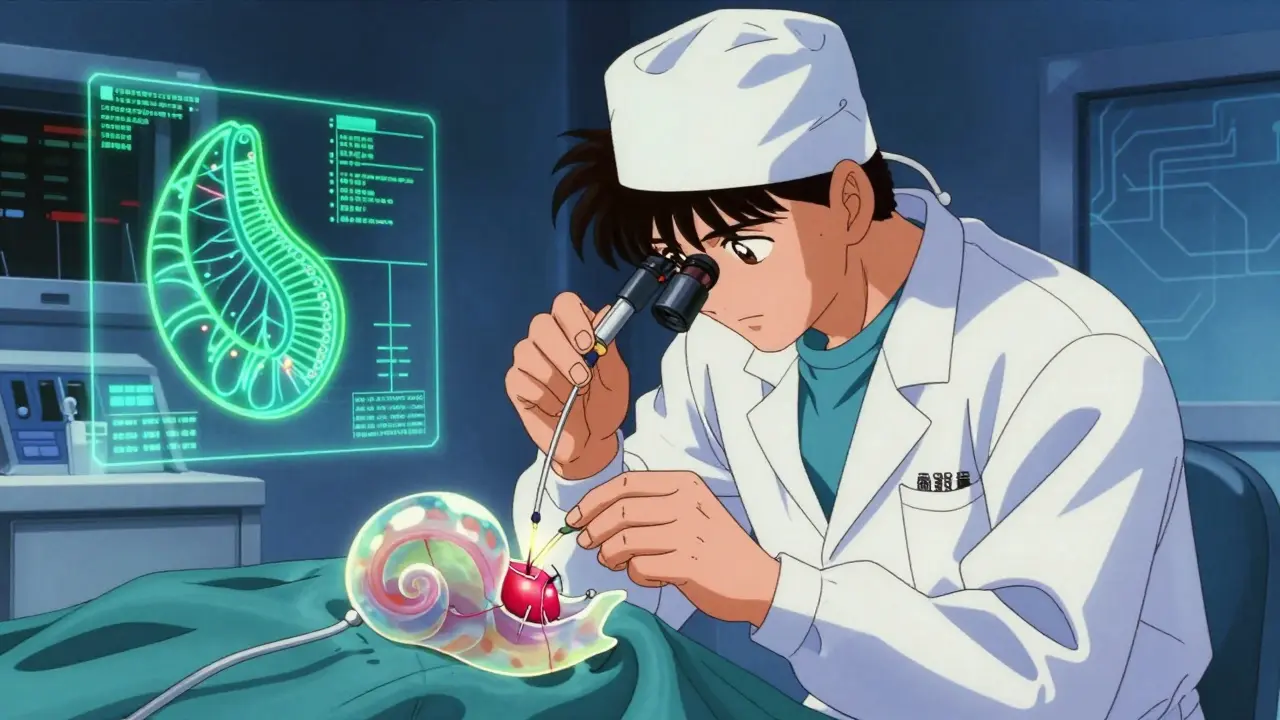

A cochlear implant isn’t one device. It’s two parts working together: an external sound processor worn behind the ear, and an internal implant surgically placed under the skin. The external part has a microphone that picks up sound, a processor that turns it into digital signals, and a transmitter coil that sends those signals through the skin to the internal receiver. The internal component, about the size of a quarter, contains a receiver-stimulator and a thin electrode array that’s threaded into the cochlea-the snail-shaped part of the inner ear.

The electrode array has between 12 and 22 tiny contacts, each spaced less than a millimeter apart. These contacts deliver small electrical pulses directly to different regions of the cochlea, matching the natural way the ear separates pitch. Higher frequencies stimulate the front, lower frequencies the back. This isn’t perfect replication of natural hearing-many users describe early sounds as robotic or mechanical-but over time, the brain learns to interpret these signals as speech, music, or environmental noise.

Modern systems, like those from Cochlear Limited, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics, use advanced signal processing with 16-32 kHz sampling rates and 12-22 frequency channels. The transmitter works via inductive coupling at 5-10 MHz, with signals passing through just 0.5 to 2 cm of skin. The internal device is secured either in a shallow depression in the skull bone or tucked under the muscle layer, ensuring stability and minimizing interference.

Who Is a Candidate?

Not everyone with hearing loss qualifies. Cochlear implants are meant for those with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss-typically a pure-tone average of 70 dB or worse in both ears-and who get less than 50% speech recognition even with the best-fitting hearing aids. This includes adults who lost hearing after learning to speak, as well as children born deaf.

The FDA approved cochlear implants for children as young as 9-12 months in 1990, and today, early implantation is strongly encouraged. Children implanted before age two often develop speech and language skills close to their hearing peers. Those implanted after age seven may still benefit, but progress is slower and requires intensive therapy. Adults who have been deaf for decades can also be candidates, though outcomes tend to be better if hearing loss is recent. The key factor isn’t age-it’s how long the brain has been deprived of sound.

People with non-functional auditory nerves, or those whose deafness stems from brain-based issues rather than inner ear damage, are not candidates. Bone conduction devices or auditory brainstem implants may be alternatives in these cases.

The Surgical Process

The surgery takes about two hours and is done under general anesthesia. Surgeons make a 4-6 cm incision behind the ear, then remove part of the mastoid bone to access the middle ear. The facial nerve runs nearby, so monitoring is used throughout-electromyography alerts the team if stimulation exceeds 0.05-0.1 mA, preventing accidental nerve damage.

The electrode array is inserted either through the round window-a natural opening-or via a small hole drilled into the cochlea (cochleostomy). The round window approach is preferred when possible, as it reduces the risk of misplacing the electrode into the wrong canal. Once placed, the receiver-stimulator is anchored in place, and the incision is closed. Most patients go home the same day or the next.

Complication rates are low. Experienced teams report major complications-like facial nerve injury or infection-in fewer than 1% of cases. Minor issues like temporary dizziness or numbness around the incision are common but fade within weeks. About 5-10% of implants eventually need revision surgery due to device failure or migration.

Recovery and Activation

Healing takes time. Patients typically wait 2-4 weeks before the implant is turned on. This delay allows swelling to subside and tissue to stabilize. At activation, the audiologist connects the external processor and begins mapping-the process of setting the electrical current levels for each electrode. The first sounds are often startling: voices may sound like cartoon characters, alarms like buzzers, and music unrecognizable.

But the brain adapts. With daily listening and consistent use, most users report significant improvement within 3-6 months. Children need 1-2 years of auditory-verbal therapy to reach age-appropriate speech milestones. Adults benefit from structured listening exercises and speech therapy, especially if they’ve been deaf for a long time.

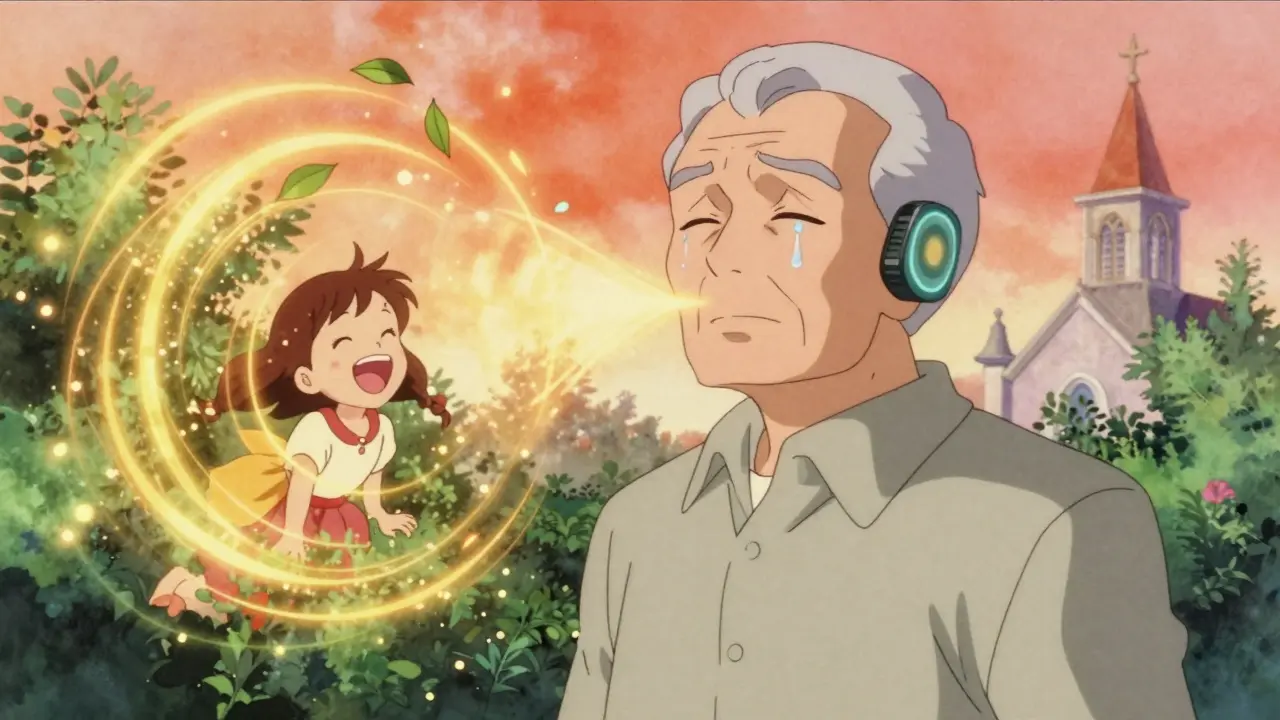

One adult recipient described hearing her granddaughter say “I love you” for the first time in 15 years. Others talk about finally hearing their own footsteps, the rustle of leaves, or the hum of a refrigerator. These aren’t just improvements-they’re moments that redefine daily life.

Limitations and Realistic Expectations

Cochlear implants don’t restore normal hearing. Music remains a challenge-many users struggle to enjoy melodies or distinguish instruments. Background noise still interferes; speech understanding in crowded rooms can drop from 80% in quiet to 30-50% in noisy environments. That’s why many users still rely on lip-reading or captioning in tough listening situations.

Some users report persistent tinnitus or dizziness after surgery, though these are uncommon. And while the internal device is designed to last 20-30 years, the external processor can be upgraded every few years as technology improves. No new surgery is needed for these updates.

Importantly, outcomes vary. A child implanted at age one with consistent therapy has a near-normal chance of speaking and learning. An adult who lost hearing at 50 and waited 20 years to get implanted may hear well but never understand rapid speech without visual cues. Success depends on the brain’s ability to relearn sound, not just the device’s quality.

Recent Advances

Technology has come a long way since the first implants in the 1970s. Today’s devices, like MED-EL’s SYNCHRONY 2, allow full 3.0 Tesla MRI scans without removing the internal magnet-something earlier models couldn’t do. That’s a huge improvement for patients who may need future imaging for other health reasons.

Hybrid implants, which combine electrical stimulation for high frequencies with acoustic amplification for low ones, are helping people who still have some natural low-frequency hearing. Research is also exploring drug-eluting electrodes to reduce scar tissue buildup around the implant, which can degrade performance over time.

Future processors may use artificial intelligence to filter noise automatically, focus on speech, or even adjust settings in real time based on the environment. These aren’t sci-fi-they’re already in development.

Cost and Access

In the U.S., insurance typically covers cochlear implants if patients meet strict criteria: documented profound hearing loss and poor speech recognition despite optimal hearing aids. Worldwide, about 324,000 people have received implants as of 2022, with over 96,000 in the U.S. alone. Still, millions more could benefit but don’t have access due to cost, lack of awareness, or limited specialist centers.

Rehabilitation is just as important as surgery. Successful outcomes require a team: otolaryngologists, audiologists, speech-language pathologists, and sometimes psychologists. Programs at major hospitals like Great Ormond Street and Mayo Clinic offer full-service care, from diagnosis to long-term follow-up.

Final Thoughts

Cochlear implants are not a cure for deafness. But for those with profound hearing loss, they’re the closest thing to a second chance at sound. They don’t make the world louder-they make it audible again. The technology isn’t perfect, and the journey isn’t easy. But for the people who’ve lived in silence, the reward isn’t measured in decibels. It’s measured in voices heard, laughter shared, and connections restored.

Comments (9)

Henriette Barrows December 28 2025

I remember my cousin getting her implant at 11 months. First time she heard her mom say her name, she just froze-then started crying. Not because it was loud, but because it was her. That moment changed everything. No fancy stats needed.

Jim Rice December 29 2025

Let’s be real-this whole thing is overhyped. I’ve known three people with implants. Two of them still can’t tell the difference between a dog barking and a microwave beep. And the third one? Still uses lip reading 80% of the time. You’re selling a miracle, but it’s just a very expensive hearing aid with brain training.

Alex Ronald December 30 2025

Jim, you’re not wrong-but you’re missing the point. It’s not about perfection. It’s about access. For someone who’s spent 30 years in silence, even a distorted voice saying ‘good morning’ is a door opening. The brain rewires itself. I’ve seen adults who lost hearing in their 40s learn to recognize their own laugh again. That’s not a miracle-it’s neuroplasticity.

Manan Pandya December 31 2025

As someone from India where cochlear implants are largely inaccessible due to cost, I find this article profoundly moving. In rural areas, even basic hearing aids are out of reach. The fact that technology exists to restore sound-but doesn’t reach those who need it most-is a tragedy masked as progress.

Sharleen Luciano January 2 2026

How quaint. You’re all romanticizing a technological intervention that pathologizes deafness as a deficit rather than a cultural identity. Deaf culture has its own language, its own art, its own community. To frame cochlear implants as ‘restoring connection’ is colonialist nonsense. Why not ask the Deaf community what they want instead of assuming they’re broken?

And don’t get me started on the ‘children implanted before two’ narrative-what about their right to choose their own identity? This isn’t medicine-it’s assimilation dressed in white coats.

Oh, and ‘robotic’ sounds? That’s not a flaw-it’s a feature. The auditory cortex adapts to the signal it receives, not to some idealized notion of ‘natural’ hearing. You’re imposing a hearing norm on a neurodivergent population. How very 20th century of you.

Also, the article mentions ‘speech milestones’ like that’s the only metric that matters. What about sign language fluency? Deaf literature? Deaf poets? You’ve reduced an entire culture to a failed hearing test.

I’m not against technology. I’m against the assumption that every deaf person wants to be ‘fixed.’ And frankly, your tone reeks of ableist paternalism wrapped in scientific jargon.

Aliza Efraimov January 3 2026

Sharleen, I hear you. I really do. But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. My sister is Deaf, uses ASL, and loves her culture-but she also got an implant at 32 because she wanted to hear her nephew say ‘I love you’ without having to ask him to repeat it five times. She didn’t reject her identity-she expanded it. You can be Deaf AND want sound. It’s not either/or.

And no, not every deaf person wants an implant. But for those who do? Let them have it without being called colonialists. The world isn’t black and white. People are messy. And so is healing.

Paige Shipe January 4 2026

Wow. Just wow. I can’t believe people are still arguing about this. I’ve read the FDA guidelines, the cochlear implant manuals, and the peer-reviewed studies. The data is clear: early implantation leads to better outcomes. If you don’t believe me, go ask the researchers at Johns Hopkins. Or better yet-go ask the parents whose kids went from silent to reading chapter books by age 5. That’s not ‘assimilation.’ That’s education. That’s opportunity.

And as for ‘Deaf culture’-yes, it’s beautiful. But not every deaf person wants to live in a bubble. Some want to talk to their grandmas. Some want to hear the phone ring. Some want to enjoy music without having to feel the bass. That’s not a crime. It’s human.

Also, the article didn’t say ‘all deaf people should get implants.’ It said ‘for those with profound loss who get no benefit from hearing aids.’ That’s a medical fact, not an ideology.

Stop weaponizing identity to shut down progress. People deserve choice. Not dogma.

Teresa Rodriguez leon January 4 2026

My husband lost his hearing after a meningitis infection at 28. He waited 12 years to get an implant because he was scared. When they turned it on, he screamed. Not from pain-from shock. He hadn’t heard his own voice in over a decade. He cried for three days straight. And now? He still can’t enjoy music. But he hears the doorbell. He hears his dog bark. He hears me say ‘I’m home.’

That’s all I needed to know.

Nisha Marwaha January 5 2026

From a clinical audiology perspective, the real game-changer isn’t the electrode array-it’s the signal processing algorithm’s ability to resolve temporal fine structure at 16kHz+ sampling rates with dynamic noise suppression. Earlier devices used fixed mapping; modern ones employ machine learning-based adaptive mapping, reducing cognitive load by 40% in noisy environments. The SYNCHRONY 2’s MRI compatibility is a massive leap-previously, even 1.5T scans required magnet removal, which introduced infection risks and necessitated revision surgery in 8% of cases.

Also, the 2023 Cochrane meta-analysis showed that children implanted before 18 months achieved 92% of age-appropriate receptive vocabulary scores at age 5, compared to 58% in late-implanted cohorts. That’s not anecdotal-it’s effect size d=1.3.

But yes, the emotional outcomes are just as critical. The neurocognitive reorganization post-implantation involves the dorsal auditory stream’s repurposing for phonological encoding. It’s not just hearing-it’s linguistic reacquisition.