How Hepatitis A Spreads Through Food

Most people think of hepatitis A as something you catch from dirty water or bad hygiene. But in real life, it’s often spread through food - and not always in the way you’d expect. The virus doesn’t need to be in the food itself. It just needs to get there from an infected person’s hands.

It takes as few as 10 to 100 virus particles to cause infection. That’s less than a speck of dust. A food worker with hepatitis A who doesn’t wash their hands after using the bathroom can transfer the virus to a sandwich, salad, or sushi roll in seconds. Studies show nearly 10% of the virus on a contaminated finger can move to a piece of lettuce with just light contact. And once it’s on the food, it doesn’t die easily. Hepatitis A can survive for weeks on stainless steel, months in frozen food, and even through brief heating - it takes 85°C for a full minute to kill it. Cooking at 60°C? That’s not enough.

Shellfish are a known risk because they filter water. If they’re harvested from sewage-contaminated waters, they can concentrate the virus. Produce like berries, greens, and herbs is another major source. These foods are often eaten raw and washed with water that may not be safe. Outbreaks have been traced back to frozen strawberries, imported basil, and raw scallions. The problem isn’t just the food. It’s who handled it.

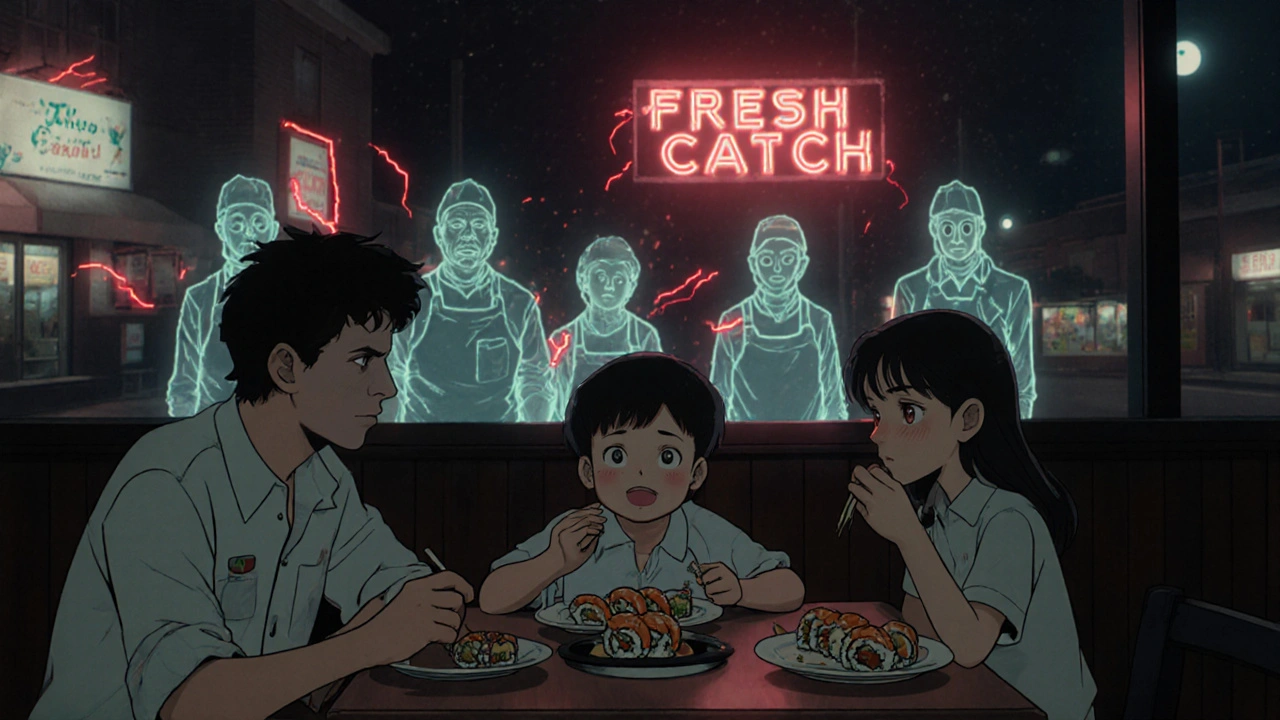

One infected food handler can start an outbreak that affects dozens, even hundreds. And here’s the silent danger: up to half of infected people show no symptoms, especially kids. They go to work, handle food, and spread the virus without knowing they’re sick. By the time someone gets jaundice - the yellow skin and eyes that signal liver damage - the virus has already moved through the kitchen, the restaurant, and maybe even a whole community.

When and How You Get Infected

The timeline matters more than you think. You don’t get sick right away. The virus hides in your body for 15 to 50 days - usually around 28. But you’re contagious long before you feel bad. You can spread hepatitis A one to two weeks before symptoms appear. And you keep spreading it for at least a week after your skin turns yellow. That’s a window of six to eight weeks where you could be infecting others without realizing it.

This is why food service outbreaks are so hard to stop. Someone eats a contaminated burrito on Monday. They don’t feel sick until Friday. By then, they’ve been working the grill for three days. Their coworkers ate the same food. Customers came and went. The health department doesn’t even know there’s a problem until someone else gets sick - and then it’s too late to trace back to the original source.

Testing confirms the diagnosis. Doctors don’t guess. They check for HAV IgM antibodies in your blood. These show up 5 to 10 days before symptoms and stick around for months. If you’ve been exposed and you’re tested within a week, the test might come back negative - not because you’re clean, but because your body hasn’t had time to react. That’s why timing is everything.

What to Do After You’ve Been Exposed

If you know you ate food handled by someone who later tested positive for hepatitis A - or if you were in a restaurant during an outbreak - you need to act fast. The clock starts ticking the moment you’re exposed. You have only 14 days to get help.

There are two options: the hepatitis A vaccine or immune globulin (IG). The CDC says both work, but they’re not the same. The vaccine is a single shot, given in the arm. It’s recommended for healthy people between 1 and 40 years old. It doesn’t just protect you now - it gives you long-term immunity, likely for 25 years or more. The cost? Around $50 to $75.

Immune globulin is a shot of antibodies taken from donated blood. It gives you immediate, but temporary, protection - just 2 to 5 months. It’s used for people outside the vaccine age range: infants under 1, adults over 40, or anyone with a weakened immune system. It costs more - $150 to $300 - and requires a larger volume injection, often in the buttock.

Neither option stops you from spreading the virus right away. That’s a common misunderstanding. Even if you get the shot, you still need to wash your hands like your life depends on it. For the next six weeks, avoid touching food with bare hands. Don’t prepare meals for others. Don’t share utensils. Don’t assume the shot made you safe. It protects you from getting sick. It doesn’t make you non-infectious.

Why Vaccination for Food Workers Isn’t Enough

You’d think restaurants would vaccinate their staff. After all, it’s cheaper than dealing with an outbreak. But the numbers don’t lie. Only about 30% of food workers in the U.S. are vaccinated. In places with high turnover - fast food, seasonal stands, migrant labor - it’s as low as 15%.

Why? Turnover is brutal. In quick-service restaurants, staff change every 6 to 8 months. Training is rushed. Many workers don’t even know hepatitis A is a risk. Surveys show only 35% can name the symptoms. Only 28% know the 14-day window for post-exposure shots. Language barriers make it worse. In big cities, nearly half of kitchen staff speak a language other than English. Safety posters in English? Useless.

And then there’s cost. Employers don’t pay for it. Workers don’t have time to go to a clinic. A $75 vaccine might seem cheap to you. To someone working two jobs and living paycheck to paycheck, it’s a luxury. Some states are changing this. As of early 2024, 14 states require hepatitis A vaccination for food handlers. California’s mandate since 2022 prevented 120 infections and saved $1.2 million in outbreak costs. But most places still don’t require it.

What Restaurants Should Be Doing - and Usually Aren’t

Good hygiene isn’t optional. It’s the only thing standing between a healthy meal and an outbreak. But most restaurants aren’t doing enough.

Washington State found that 78% of food businesses still allow bare-hand contact with ready-to-eat food. That means workers are picking up sandwiches, salads, and sushi with their fingers. Gloves and tongs are the rule - not the exception. Yet only 42% follow it.

Handwashing is another weak spot. The CDC says washing with soap and water for 20 seconds cuts transmission by 70%. But how many people actually wash for 20 seconds? Most splash water for 5. And if the sink is broken, or there’s no soap, or there’s only one sink for 20 workers? That’s not a problem - it’s the norm.

Training helps. Hands-on practice improves compliance by 65%. But only 31% of restaurants do it. Most rely on a 10-minute video or a signed form. That’s not training. That’s paperwork.

Restaurants need to fix three things: handwashing stations (at least one per 15 workers), glove use for ready-to-eat food, and vaccination for staff. If they don’t, they’re not just risking customer health - they’re risking their business. An outbreak can cost $100,000 to $500,000 in investigations, lost sales, and lawsuits. Vaccinating one worker costs $75. That’s a no-brainer.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

As a customer, you can’t control the kitchen. But you can make smart choices.

- If you’re pregnant, over 40, or have liver disease, ask if the restaurant uses gloves or utensils for ready-to-eat food.

- Wash your hands before eating - even if you’re not preparing food. Use soap, scrub for 20 seconds, dry with a paper towel.

- When you travel, avoid raw shellfish and unpeeled fruit in places with poor sanitation.

- If you’re planning to eat at a food truck or street vendor, look for signs of cleanliness: gloves, handwashing signs, clean counters.

- If you think you were exposed, call your doctor or local health department immediately. Don’t wait. The 14-day window is real.

And if you work with food? Get vaccinated. Even if your employer doesn’t require it. One shot now can save you, your coworkers, and your customers from weeks of fever, nausea, and liver damage. It’s the easiest way to break the chain.

What’s Changing in Hepatitis A Prevention

The tide is turning - slowly. New tools are coming. Pilot programs are testing wastewater in restaurant drains to detect the virus before anyone gets sick. If the system picks up traces of HAV in the sink drain, health officials can test staff before symptoms show. It’s like a smoke alarm for the virus.

Point-of-care blood tests are in late-stage trials. These could give results in 15 minutes, not days. Imagine a food worker feeling off - they swab their finger, get a result in minutes, and stay home before they infect anyone.

Some cities are linking vaccination to food handler permits. If you want to work in a kitchen, you need proof of vaccination. Twenty-two jurisdictions already do this. And financial incentives work. One study gave workers a $50 bonus for getting the shot. Vaccination rates jumped 38 percentage points.

The CDC’s goal? Cut foodborne hepatitis A outbreaks by half by 2025. It’s doable - if we stop treating this as a personal hygiene issue and start treating it like the public health threat it is.

Comments (10)

Alyssa Torres November 20 2025

I work in a diner and this post made me cry. Not because I’m scared-I’m vaccinated-but because I’ve seen coworkers skip handwashing after the bathroom. One guy even wiped his hands on his apron. We had a kid get sick last year after eating a grilled cheese. No one knew why. Now I bring my own soap to work. And I remind everyone. It’s not about blame. It’s about care.Also, if you’re a manager reading this: buy the damn gloves. It’s cheaper than a lawsuit.

Aruna Urban Planner November 22 2025

The epidemiological burden of HAV in foodservice ecosystems is disproportionately amplified by asymptomatic shedding and infrastructural deficits in hygiene compliance. The cost-benefit analysis of mandatory vaccination is statistically compelling, yet socio-political inertia and labor precarity inhibit systemic adoption. A structural intervention-embedded public health literacy in occupational licensing-is required, not merely individual behavioral nudges.Nicole Ziegler November 24 2025

ok but like… i just ate a burrito from a food truck yesterday 😳 i’m so scared now 😭Bharat Alasandi November 24 2025

bro i work in a chai wallah and we don't even have running water half the time. how u expect us to wash hands for 20 sec? the real issue is not the worker, it's the system. no clean water, no soap, no training. vaccinate the staff? cool. but first give us sinks.Kristi Bennardo November 25 2025

This is an absolute scandal. Restaurants are public health time bombs and no one is holding them accountable. I’ve seen employees wipe their noses on their sleeves and then serve sushi. This isn’t negligence-it’s criminal. The FDA should shut down every establishment that allows bare-hand contact with ready-to-eat food. And if they don’t, I will personally file a class-action lawsuit. This is not a suggestion. This is a demand.Shiv Karan Singh November 25 2025

lol you think this is about hygiene? nah. it's about the vaccine industry pushing profit. hepatitis A is barely dangerous for healthy people. they made it sound like a zombie virus so you’d panic and buy shots. also, the CDC is funded by pharma. think about it.Ravi boy November 26 2025

i work in a kitchen in delhi and we use our hands for everything. no gloves no soap just water. but i wash after potty i swear. also my mom says if u get sick its god's will. so i just pray and keep cooking. hope no one gets sick lolMatthew Karrs November 27 2025

Let’s be real-this whole thing is a distraction. Hepatitis A outbreaks are rare. Meanwhile, the real killers are processed foods, sugar, and corporate lobbying. This post is just fearmongering to sell vaccines and push more regulations. They want you scared so you’ll obey. Wake up. The real threat is the system, not the food handler.Matthew Peters November 27 2025

I’m a chef and I’ve been vaccinated since 2021. But here’s the thing-most of my crew don’t even know what HAV stands for. We had a guy last month who came in with a fever and kept prepping salads. No one said anything. We need mandatory training. Not just a 10-minute video. Real drills. Like fire drills. What if we had a ‘virus drill’ once a month? Practice glove changes, handwashing, reporting symptoms. Make it normal. Not a chore. A habit.Liam Strachan November 28 2025

Fascinating read. I’m from the UK and we’ve had a few outbreaks linked to imported berries, but nothing on this scale. I think the real takeaway is that hygiene standards need to be universal-not just in places with high turnover. Maybe we need an international food handler hygiene certification? Something that travels with the worker, not just the restaurant. It’s not just about money or laws-it’s about dignity. Everyone deserves to work safely.